In school we were taught to assess the joints above and below the affected joint; this is a good starting point and accounts for all of our 2-joint muscles, but I would argue that the connections of the body should drive us to look even deeper than that. Our body is a whole unit and is built to function that way. The presenting impairment could be primary or secondary, but either way, we should look at the big picture.

For Instance, consider these common findings:

- A rounded shoulder: An anterior glenohumeral position and anteriorly tilted scapula typically go hand-in-hand. Why are they tilted? Pec tightness, scoliosis, protective guarding, or is it simply poor posture? This position could limit the potential for thoracic extension. It could lead to a relative lateral trunk flexion, promote a forward head position, or it could create rib dysfunction. There is so much potential for an extensive impact in just this one thing.

- A flexed knee: The muscular response here is big; there’s a shortening of the hip flexors, hamstrings, and calves. Which came first and why? Why is the knee flexed? The muscle tightness alone creates more joint stress and dysfunction, including decreased heel strike in gait. The lower extremity dysfunction goes down the line. There will also be pelvic asymmetry. An uneven pelvis creates an asymmetrical pull on the lumbar spine and yields even more muscle imbalance. The spinal dysfunction goes up the line.

- Latissimus dorsi tightness: This, the largest muscle in the upper body, has connections to the pelvis, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, scapula, ribs, and humerus. Can shoulder pain be related to back pain? Absolutely.

There are countless examples of how all the connections of the body affect each other. There are also plenty of systemic examples of how dysfunction in one system can directly impact another; just think of the many connections of the vagus nerve, and how much the heart and kidneys rely on each other for proper function. But let’s illustrate a couple of instances where our body systems are altered as a result of musculoskeletal dysfunction.

Respiration

When we breathe, our ribs need to expand and contract. More than that, when we inhale the spinal curves flatten, the sternum opens up, and the sacrum counternutates (giving us reciprocal L5 flexion). Vice versa for exhalation. What if the movement of even one of these segments is limited? Respiration will change. This will impair the ability to efficiently oxygenate the rest of the body, creating the potential for all kinds of functional limitations.

Digestion

The psoas muscle attaches the lower spinal segments to the femur. Its impact is huge, and it is considered by many to be the most important muscle in the body. We know it can cause back pain, pelvic pain, or hip pain, but a tightness in the psoas can also put pressure on the lower abdomen, potentially causing abdominal pain and bloating. More directly, there are fascial connections between the psoas and the colon. Immobility in one can lead to immobility in the other. Interestingly, there are also fascial connections between the psoas and diaphragm- and that brings us back to respiration. So many connections!

Sympathetic Response

I’ve previously discussed the impact of stress and anxiety on our fight-or-flight response, but I want to explore the musculoskeletal impact. The sympathetic neurons exit the thoracolumbar region of the spine. Say your patient has a flattened thoracic kyphosis (another common finding); that alone can activate the sympathetic response. What if they have pain in that area? That’s a double whammy to the system and creates a vicious cycle of pain and stress.

Research shows that the sympathetic nervous system is overactive in the presence of heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s disease, and depression. This is why knowing your patient’s past medical history is so important.

If the sympathetic nervous system is heightened, then the rest-and-digest parasympathetic system is inhibited. Completing the connection, another direct trigger of the fight-or-flight response is psoas activation (your body is preparing to run). Both of these bring us back to an impact on digestion.

Connections of the Body

There are certainly times that we can get something straightforward, but never forget the vast connections throughout our body and how all the systems work together. The longer pain and dysfunction have been there, the more global the impact becomes. So if you know the primary dysfunction you can keep an eye out for any secondary response. Even better, if you aren’t sure which is the primary dysfunction, the bigger picture may give the clues you need.

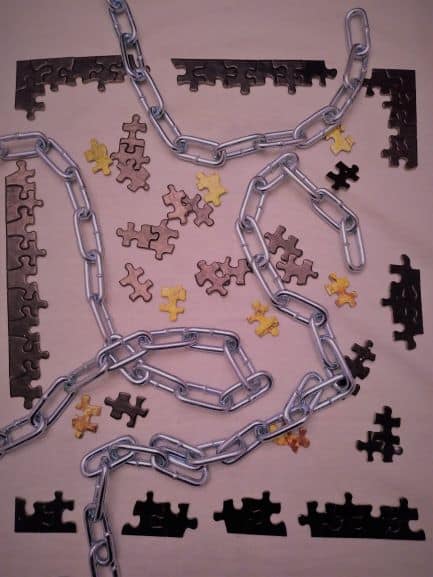

I know we all function under time constraints in our practice, but it doesn’t take long to do a gross screen. You will start to see the patterns and those five minutes may be essential to solving the puzzle of your patient.

There’s bigger words on this post. It did help me understand a little more why my back is affecting why my legs don’t work as well as they should.